We heard a mixed, bittersweet perspective on group work, so explored whether we could contribute something to help with group formation.

Background

In late 2021 we began to explore experiences and challenges around student group work, having noted what seemed to be a trend in their rising use. We conducted a literature review, drawing on university group working policies, current solutions, and academic studies. Then, in order to understand the lived experience of those involved in actual group work we conducted interviews with students and staff from several UK universities and colleges. We wanted to know how people felt about group work – what was working, what wasn’t, and why? what was frustrating?

What we heard

We heard a mixed, bittersweet perspective on group work. The relevance and importance of collaborative work was understood and appreciated by students, who recognised its value to the application of their skills in post-university life, and as a skill for employability. Contrasting this, we heard of many challenging aspects, across many dimensions – interpersonal, practical, pedagogical, logistical.

From staff we heard that creating authentic group tasks is a challenge. Students find many group assignments are not a good reflection of real-world tasks. Students dislike group marks or having to assess peer performance.

The picture is further complicated by changes such as the increase in remote participation during the pandemic, as well as an increase in group assessments (which we heard was in part due to the way it can reduce marking burden, possibly partly driven by Oversubscribed courses due to grade inflation)

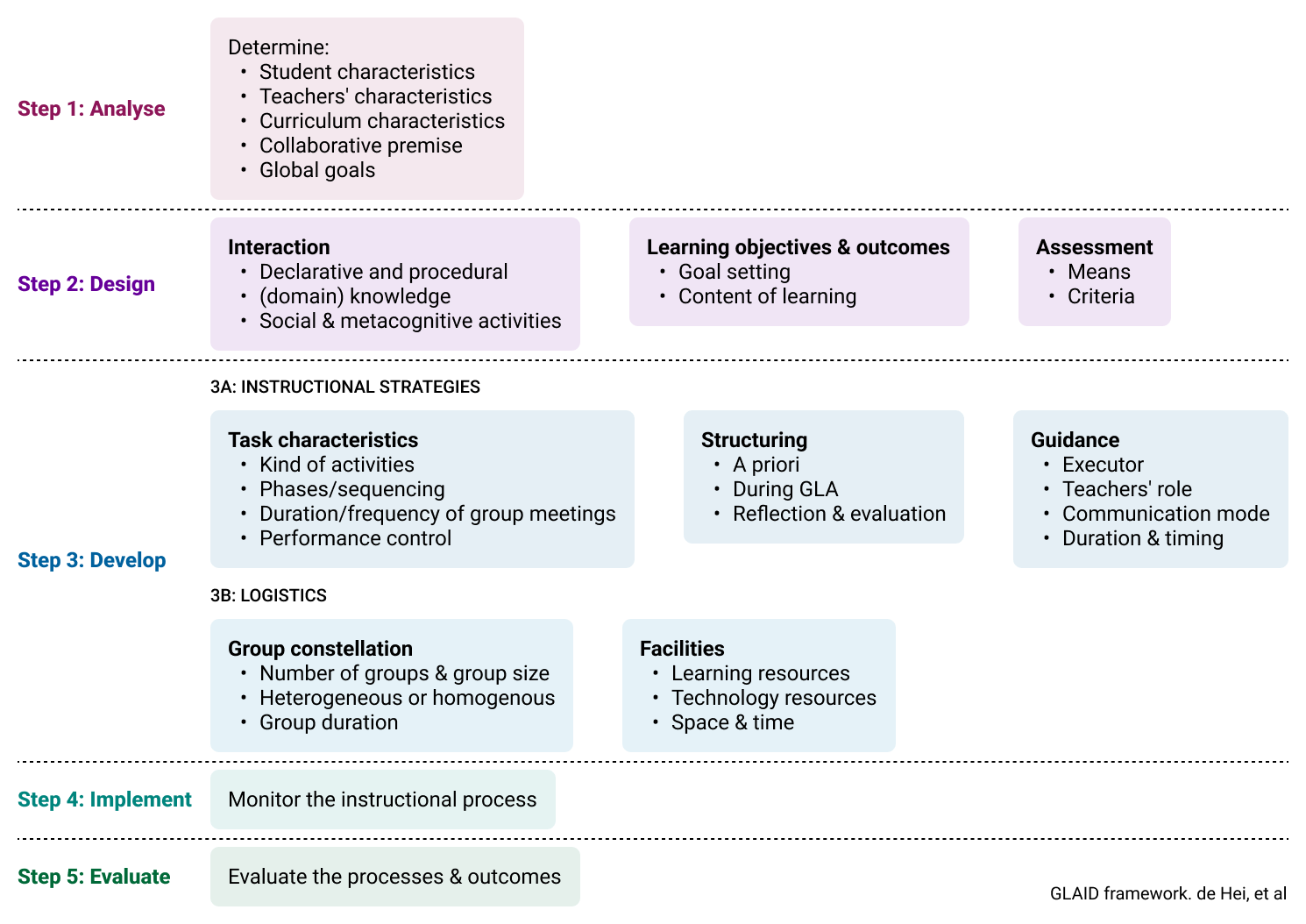

We found that the GLAID framework (de Hei et. al, also discussed here) provides a helpful unpacking of the elements within group learning activities.

The challenge of creating groups

One issue kept coming up in our research, that was how groups were allocated. In the GLAID model above, this is termed ‘team constellation’. We felt this was an interesting, tangible piece of process that we could explore further with a product mindset.

Teams can be allocated by students themselves, or by staff. By preference, randomly, or – where possible – by deliberate choices. Those choices might be personal preference; or by decisions about how groups should be composed. With inclusion being a notable driver for many, we heard lecturers seeking, for example, gender balance across teams. For some projects, skills may want to be mixed, for example when wanting teams to be equipped to produce an output requiring multiple specific specialisms. And in other cases, the mix of other factors, like ability, was being considered by staff.

One very common issue relates to students facing difficult situations when in groups with peers with lower engagement – staff too recognised this, and may consider relative ‘commitment’ to be an important consideration when mixing groups.

Our research suggested that random or self-created groups often do not result in an inclusive learning experiences, and that students perform better in diverse groups.

Group constellation stood out as a worthwhile area for exploration for two key reasons:

- It has an impact on how well the group works, support required from staff, and the final mark.

- Lecturers seemed to be limited by a difference between how they wanted to form teams, and what the tools at their disposal (i.e. VLEs) allowed them to do.

We explored the market to understand what practical tools might exist. There were several to consider, including:

- CATME (A tool from Perdue University which gathered criteria from students via a survey to create groups, quite geared to a US context)

- ITP metrics (from University of Calgary – a free to use research-based tool that also gathered criteria from students using a survey to allocate groups)

- VLEs (whose capabilities vary but are limited)

- TeamBuilder (A VLE plugin from University of New South Wales, extending default capability for group constellation, limited to Moodle)

Having solutions in the market indicated an existing need. From a Jisc perspective we felt that there were still issues that needed to be explored further to understand whether what was available met the current day challenges – particularly with a ‘UK in 2022’ focus.

A product idea for creating groups

We adopted a design constraint that we would limit the amount of data integration to reduce the barrier to implementation, and that our approach would need to be agnostic of VLE choice. The concept process began by ideating potential solutions using visual wireframes, where we could continually test and iterate our ideas.

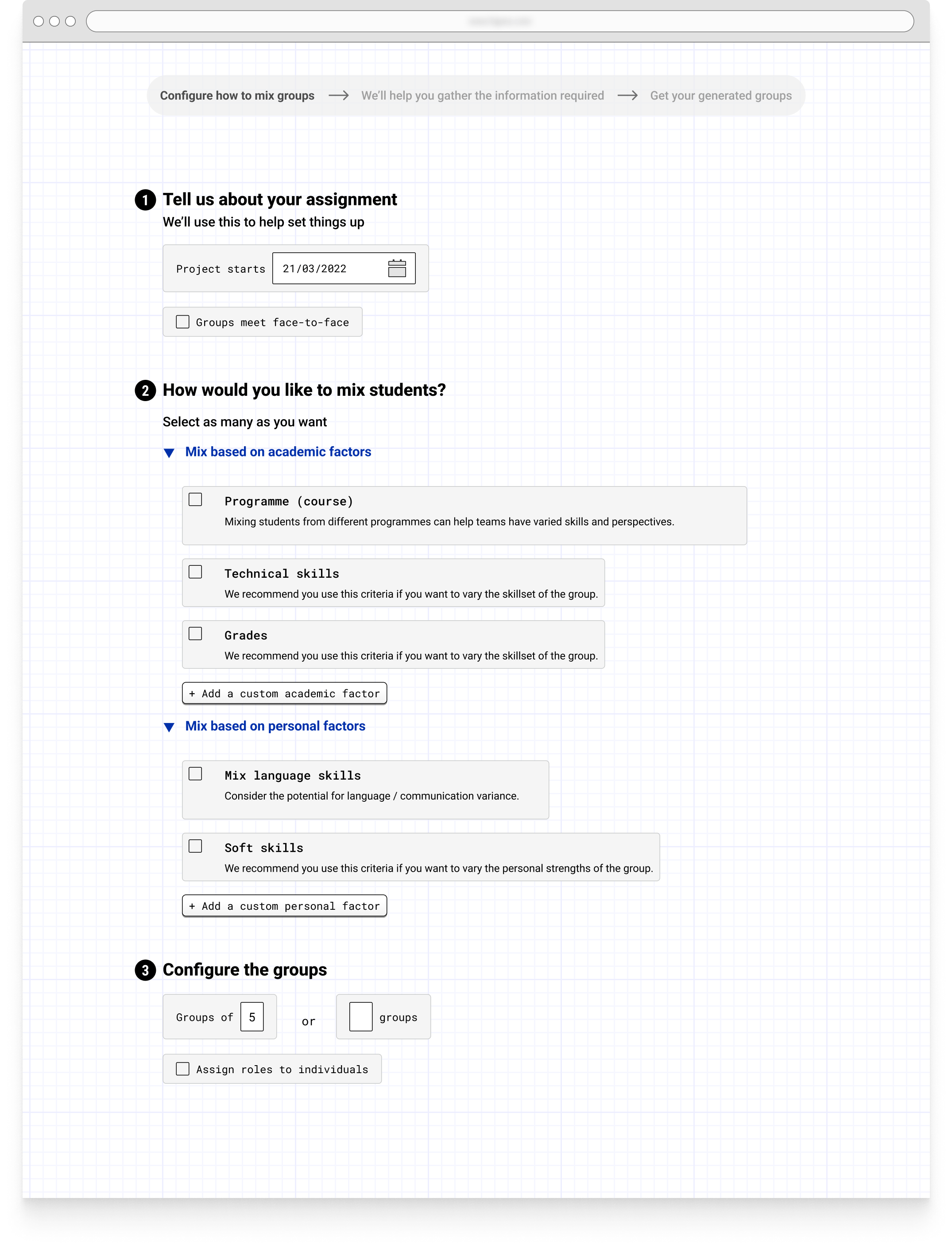

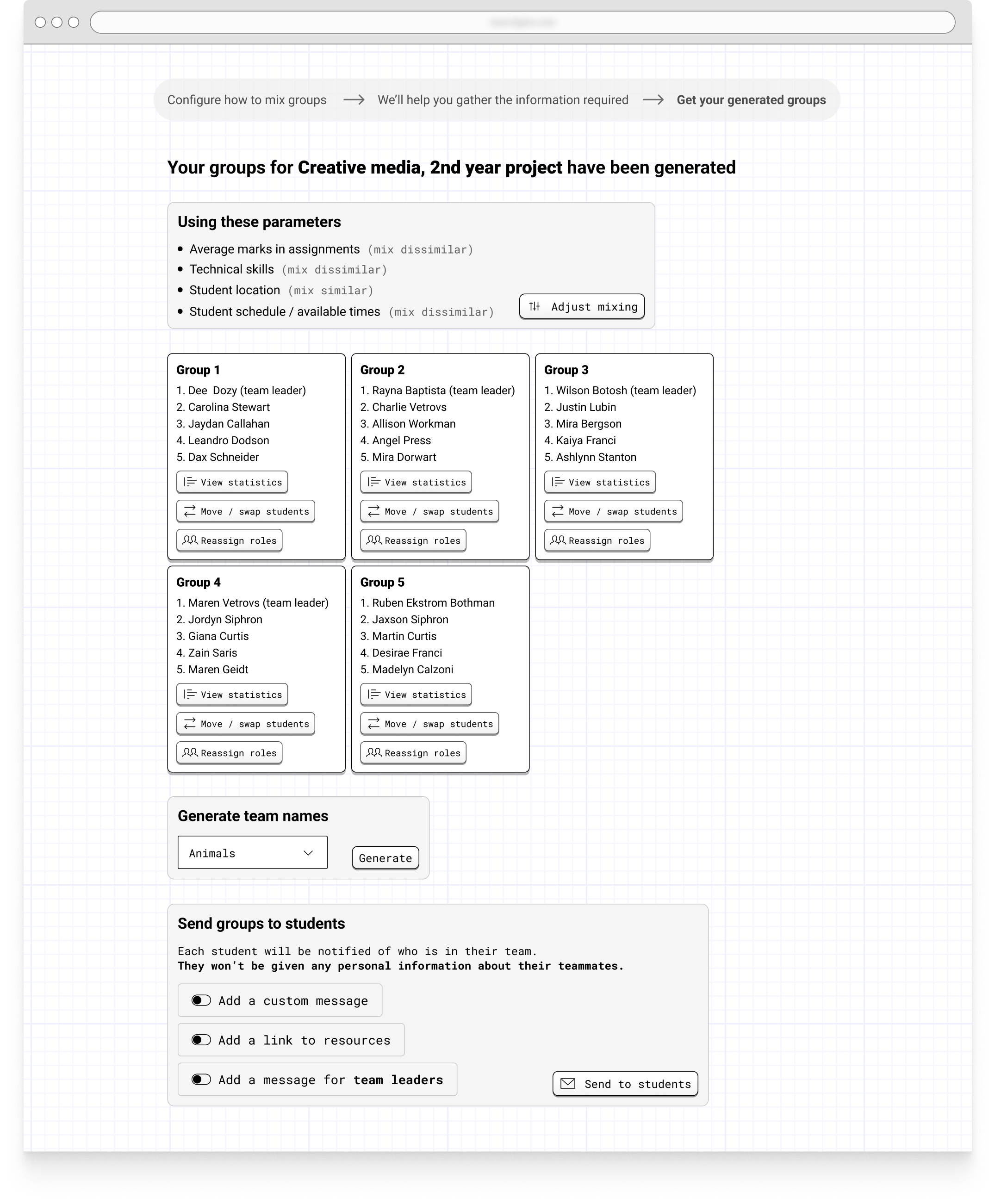

Through an iterative process – involving design exploration, research analysis, and concept testing with users – we worked towards a solution that works as follows:

- Lecturers decide the criteria of team formation.

- Students fill out surveys about their skillset.

- And then finally, the groups are formed by applying the data from step 2 to the instructions given to our algorithm in step 1.

ℹ️ All mockups in this article are wireframes created for concept testing purposes – not an indication of the precise visual design or content of a finished product.

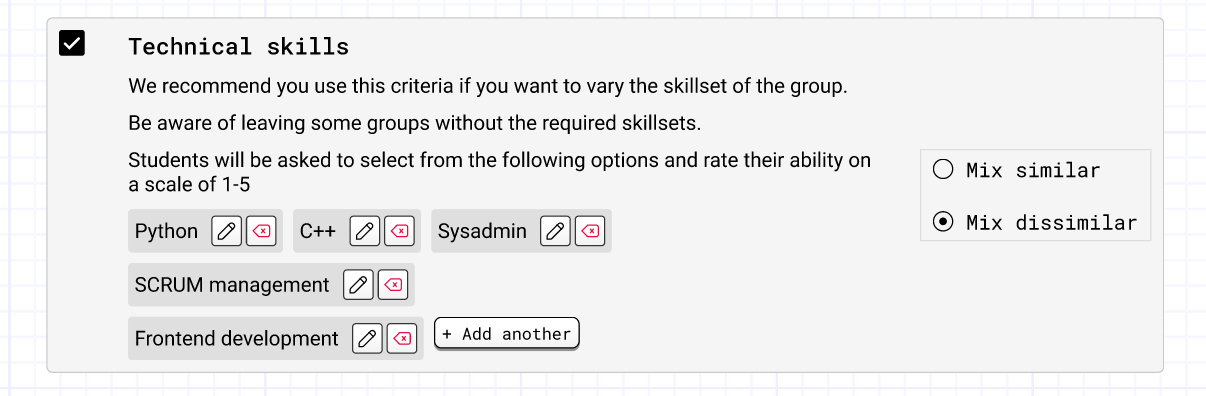

Selecting an ‘factor’ would open up some specific controls:

In this case, a way of scoping the way technical skills that students could respond to, and an instruction for whether the system should seek to group people together based on similarity or variance of responses.

From the lecturer’s perspective, you would select your criteria for the groups based on several options available. Whether it’s number in each group, amount of groups desired, gender splits, skills, grades etc. This reflects the needs and intentions laid out by the staff we had interviewed.

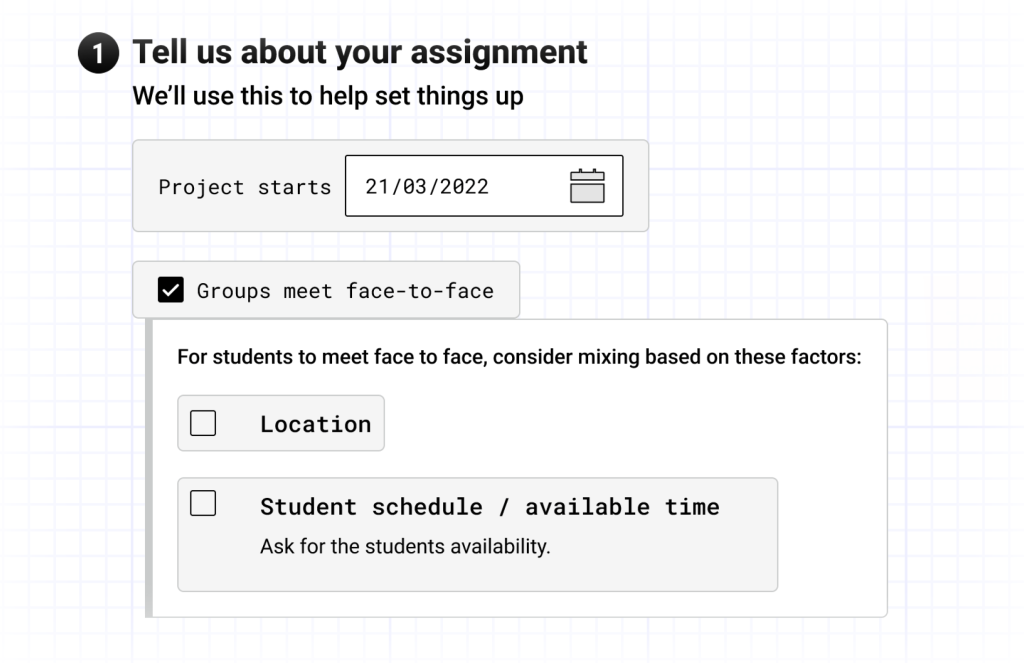

We also explored some specific reframing of how to present options to lecturers. Beginning with parameters that might help with the proposed delivery schedule:

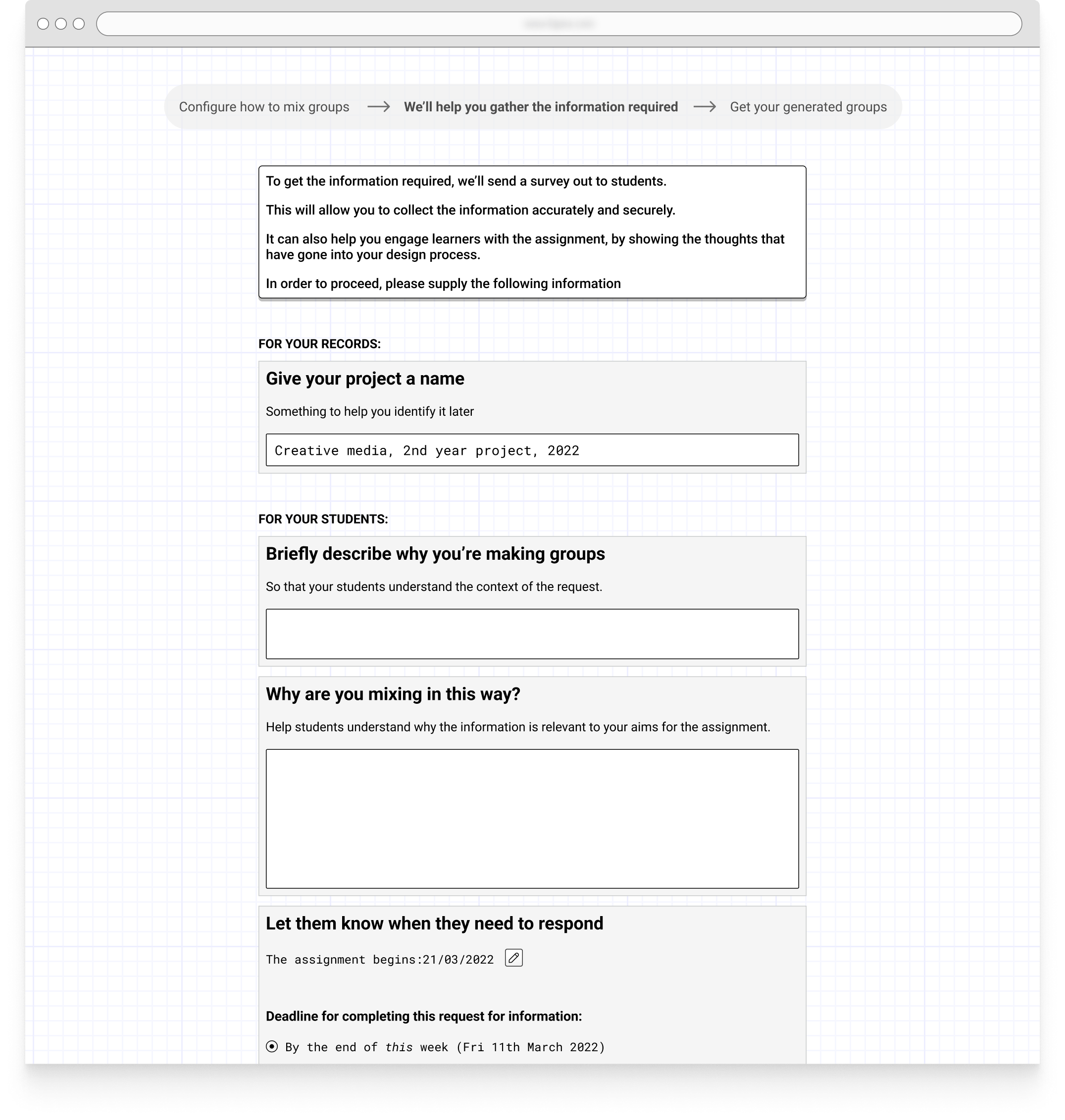

Next, once the lecturer is satisfied, the student surveys can then be distributed out. Perhaps by sharing a URL, or displaying a QR code on screen. Once all the submissions are returned, the team maker will generate the groups.

The lecturer can then make any final tweaks (we learned through primary and secondary research of the need for flexibility) before announcing the groups through individual email confirmation.

Centering the learner

It could be easy to design this with only the lecturer’s immediate, transactional needs in mind. But it is vital in designing edtech that the learner is recognised as a primary user; not just as a stakeholder to use software, but as a learner, whose usage of a system should be, can be, is, an active part of their engagement with a learning exercise.

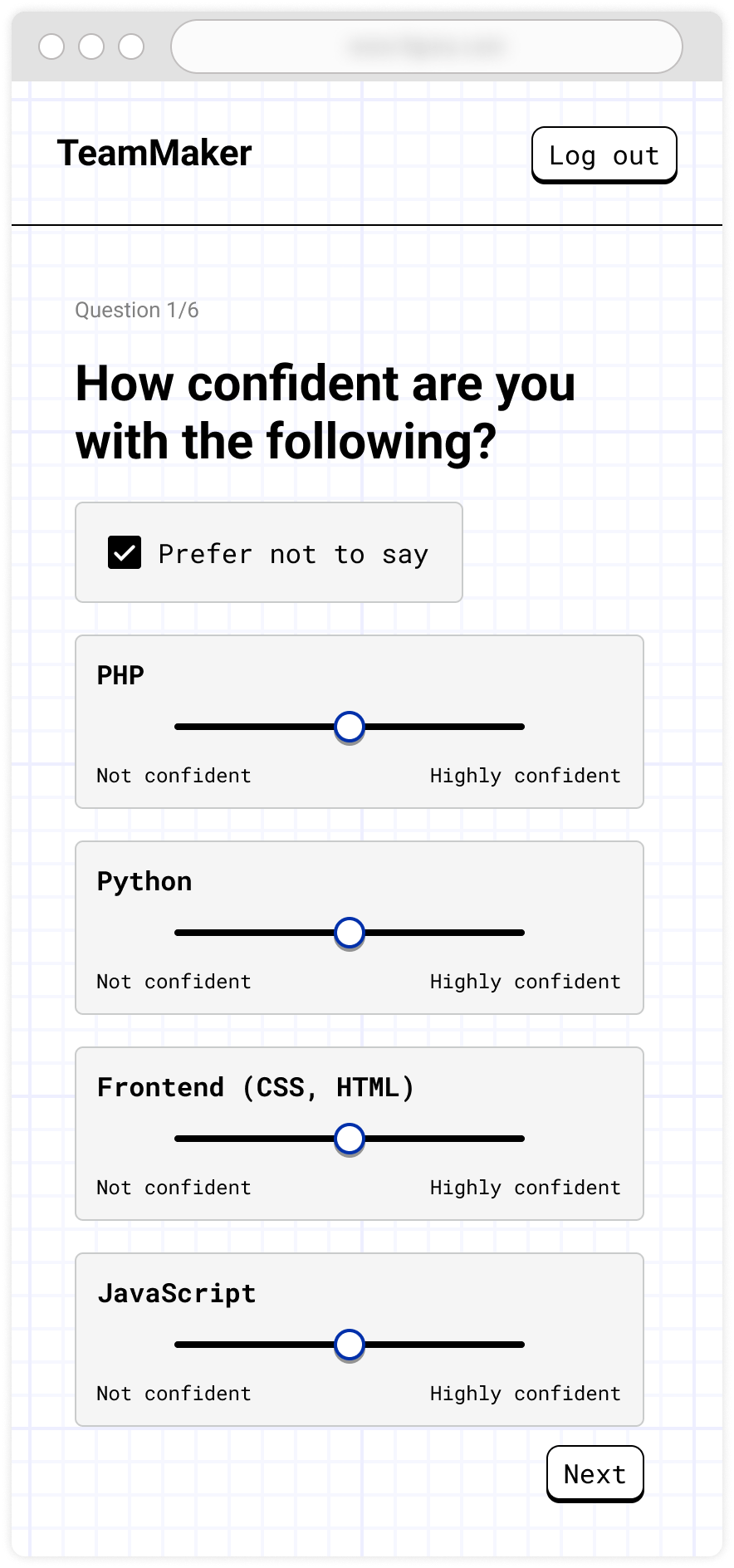

So from the students’ perspective we sought to make an experience that was not only simple, but clear and empowering. If simplicity were the sole goal, they would just receive questions and submit their responses.

Our interviews with students told us that they did have an interest in why group work was happening in the way that it was. As discussed by De Hei, the perceived value of the design of group work drives the satisfaction and perceived learning by students and teachers. We had been told from staff that we had interviewed that group work would frequently bring down NSS scores.

So one of the key tasks for lecturers when setting up the tool is to provide learners into the context of their request.

This is intended to both contextualise the request (“Why am I suddenly being asked about X?”), as well as make the design that goes into group work more transparent.

Readers may be wondering why students are being asked to respond to their answers, rather than our concept aiming to automatically pull in data from existing data stores. There is a mix of practical and tactical reasons for this. On the practical side, we took a position to not assume that the data that might be ingestible would be of sufficient quality, timeliness, abundance, or portability. But moreover, we saw this as potentially undercutting the transparency afforded by manual engagement, as well as leading us to lose out on exploring the opportunities of data control that a manual process would give.

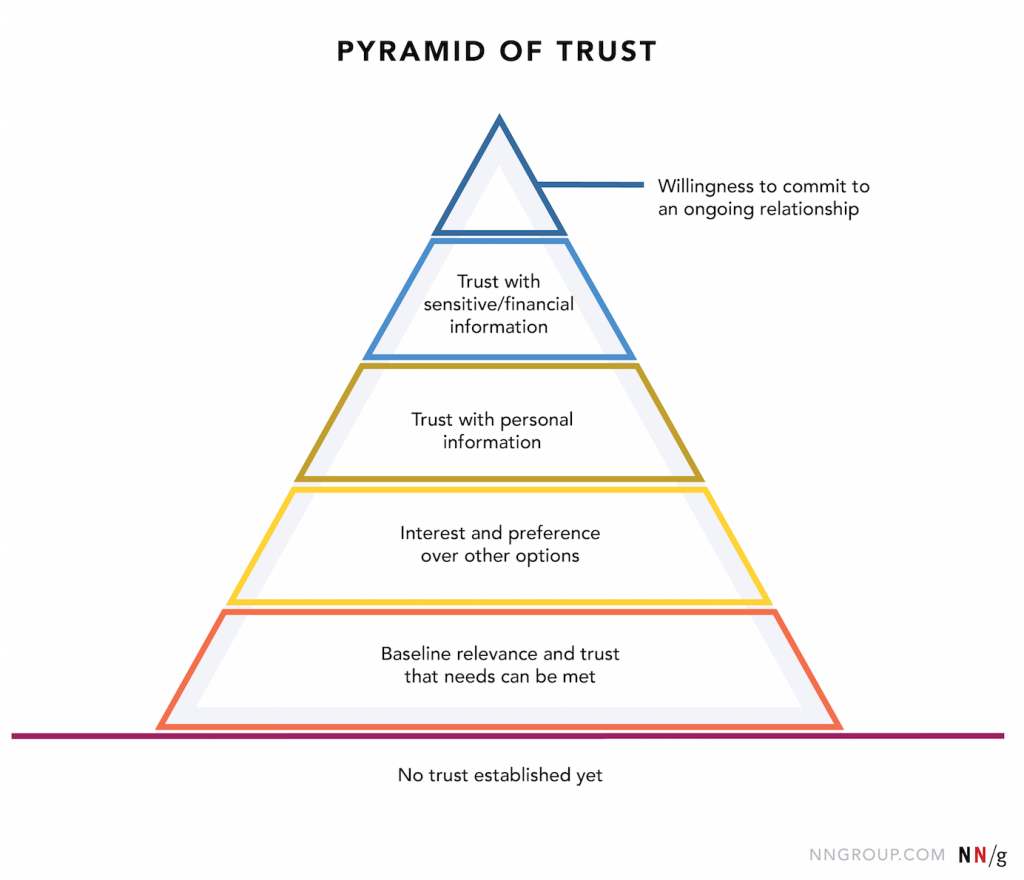

In terms of empowerment, we recognised that the questions being asked may be of a sensitive nature, which learners – for totally valid reasons – may want to withhold. When designing digital tools, it is always beneficial to reflect on this issue of trust.

This diagram from Nielsen Norman group (discussed in their article) illustrates the ladder to be climbed when establishing trust. Some elements of our approach are touched upon elsewhere in this post, but there are two more worth highlighting now:

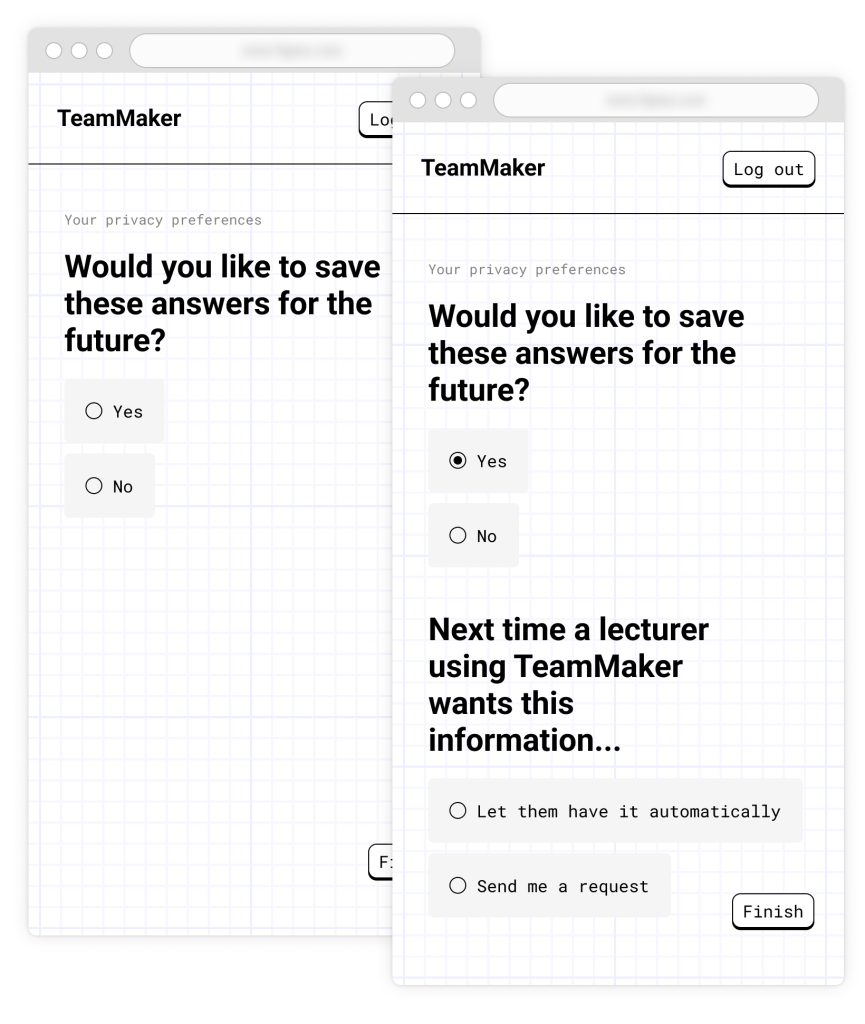

First, privacy by default. A ‘prefer not to say’ response is not only available for every question but is the default response – it is an active choice to share, rather than to withhold.

Secondly, control over responses. While some students do not mind their responses being stored to save time answering requests repeatedly, data is a sensitive and personal asset. Here you see our workflow enabling control over data storage, and – if stored – how it can be accessed in future.

What have we learned from testing the ideas with staff and students?

One size does not fit all – so where might it be useful

Sharing our concepts with lecturers reinforced something we had identified in our early research – that the approach to team constellation varies. There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ ‘best practice’ here, because learning objectives and contexts vary. And in fact, presenting a concept with multiple mixing tactics enabled lecturers to verbally explore different, or more complex, mixing practices than they would currently be able to easily perform.

So, any tool in this space must be flexible; and may not just enable existing desires, but new ones too.

Is the additional effort worth it?

A general impetus for product designers is to remove friction. This is, after all often the rationale for adopting a technological solution – to make things take less effort. But our solution did the opposite. By designing with the worst in mind (i.e. that integrations with accurate up-to-date data would be a risky assumption to bake into our concept), our workflow generated a manual process on the part of both lecturers and students. This was a critical thing for us to test.

Through testing and research we found that this friction was not only deemed tolerable, but also a potential source for additional value. Lecturers welcomed the fact that the manual nature of the workflow encouraged attention onto constellation decisions, and exposed learners to the context and decision-making that goes into group learning activities.

Stand-alone or integrated?

As discussed above, our pathway through design was to remove dependencies and assumptions in favour of a standalone approach. Our concept testing took us not just to lecturers but other staff with a stake in how learning systems sit in an institution.

In discussions with staff, we found clear value for institutions in exploring integrations, were we to take this product forward.

Final thoughts

At this time, we have decided to focus our efforts on other projects rather than pushing this concept forward.

One question we will be reflecting upon is the ‘bigger picture’. GLAID (above) helpfully seats our concept within the broader picture of group learning activities in general, and there is a yet broader picture about the future of assessment. A strategic question for us to consider is what the right way to enable learning practice to flourish in the ways people desire. Does the nimbleness of delivering smaller targeted products outweigh the benefits of more slowly working towards a much more all-encompassing apparatus that supports more of the GLAID framework? This is a question that speaks not only to what can be delivered, but what is desirable for institutions, and one we can reflect on as we go forward and consider this project in the future.

We also know that tools like CATME, ITP metrics, and Team Builder are available. We considered that Jisc’s ability to focus tightly on the UK context and our existing data & analytics portfolio would warrant our exploration, but it reassures us that by pausing effort on this, there are products that our members can access.

We will continue to look at the challenges around group work but at present are not intending to develop a product around group constellation.

We’re interested in finding more evidence around group work. What criteria or approach do you use to create inclusive groups? What user case i.e. types of group work activities would benefit from having a tool to help create groups? Do you have an example from your teaching?

If you have research or examples to share please email innovation@jisc.ac.uk

One reply on “✨ Exploring constellations – Our recent work on student group assignments”

This tool would be invaluable for some curriculum areas. There are subject areas where group work is not an optional extra and having a rational and method to generate those groups in this format would save lecturers many hours of pondering but also, remove the sense that ‘the lecturer has placed me with/separated me from person X or Y because a particular preconceived idea about me’