This is the second post about our “VLE Reimagined” project. For the background and more designs check out part 1.

These ideas explore two key themes: social connectivity, and place.

It’s not new to observe that social connectivity matters. But in digital products social connectivity is nuanced and ever changing. Myspace was different to MSN Messenger, which are different to TikTok, and Discord, each having different powers, limitations and use. It’s not just that social media apps have shifted, the way we can interact with people within apps that are not “social media” has changed too.

Consider Slack. Or Google Docs. Or YouTube. Even the very word doc I’m drafting this blog post in is social. My word document has also transitioned from being a thing you edit and ping to colleagues to a place. “I’m in the word document with the team”.

*Jisc’s 2018 report on next gen digital learning environments (page 22) talked about this idea within the context of VLEs too

What if the VLE was multiplayer?

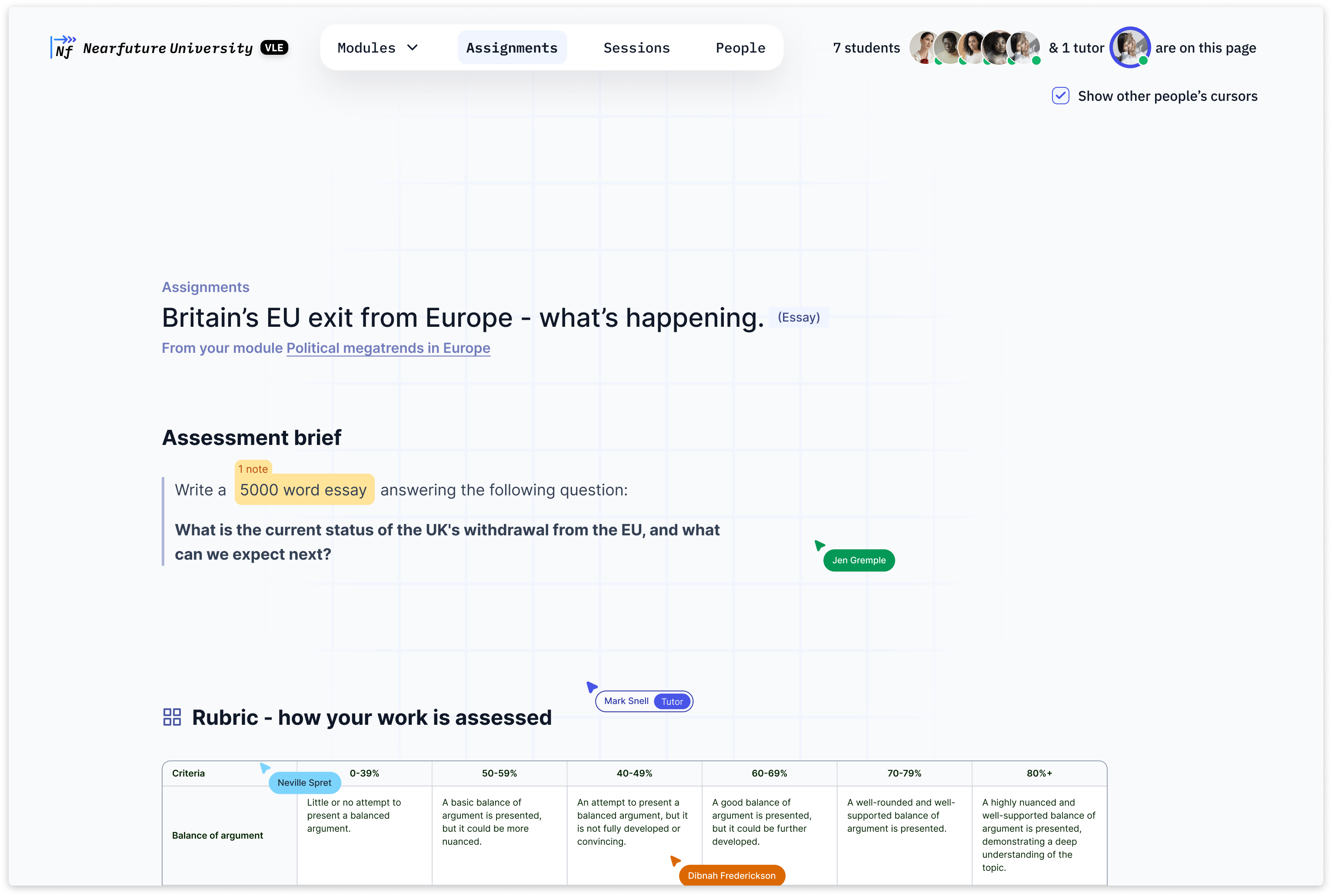

The multiplayer VLE explores how the VLE might feel if live-collaboration features were enabled much more liberally throughout the app.

Our research showed us that digital collaboration on all kinds of things – from word processing to spreadsheets; databases to planning and design has matured to a rich state. So we explored what these capabilities might be like within a VLE.

What’s old is new

Since 2013 Microsoft office apps have shown us who is working on the same document at the same time. At the time this wasn’t even new, having been present in Google Docs, for example, 3 years earlier.

Inline comments allow us to collaborate, – but also provide a secondary set of knowledge – perhaps holding insightful questions or answers clarifying the main body of content. We might then think of its potential role in learning via social metacognition, or even as a sort of feedback mechanism by which teachers can see how people respond to their materials.

Going one step further, “Multiplayer cursors” will be familiar to people who have used online collaboration tools like Miro or Mural. It’s a collaboration pattern that’s even made its way to maps.

These features can change our relationship with a document, by knowing that others are there too, potentially looking at what we are typing. We might say they turned documents from a “thing” to a “place” in which people are collocated and can collaborate live.

This raises questions such as…

- How might user behaviour change if they could see others / know they could be seen?

- Do we think of the VLE as a “thing” or a “place”?

- Does that affect how we use it?

- And is that how we want to think of it?

- How might we enable privacy, and what level of privacy would be appropriate?

- Would different approaches be preferable? We explored a broad-brush application; other approaches might be to enable this behaviour only in certain areas or circumstances.

A quick huddle?

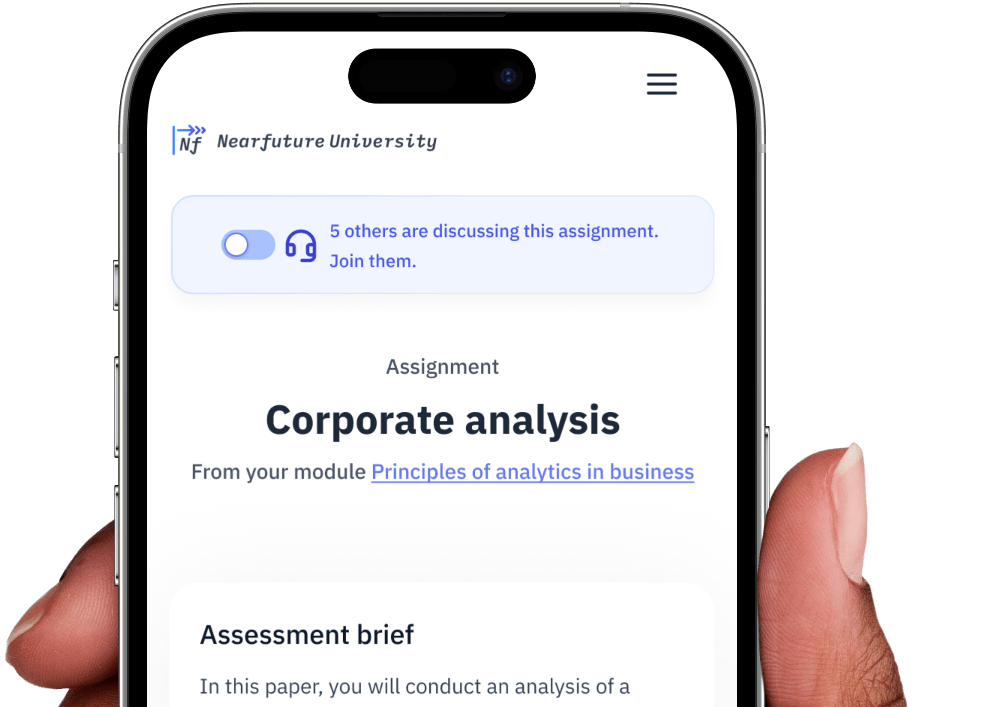

Huddle mode enables people who are looking at the same thing to be able to connect via audio chat.

Our research told us many students desire more synchronous learning when studying online. Several told us that asynchronous learning is less sociable, others that peer-to-peer social interaction helps with motivation.

Video conferencing apps are just one way of facilitating socialisation through synchronous learning, and come with their own limitations (bandwidth; quality; the need to be ‘seen’; being a separate app to fire up). We also heard that large video sessions can be intimidating, creating a barrier for engagement for some.

A dash of spontaneity

So we explored how we might bring audio chat into the VLE, and in particular how we might make it more spontaneous. This is reminiscent of gathering around a notice board and being able to be in the presence of others processing the same information and being able to chat and query it together. More specifically, it’s akin to the huddle feature within Slack, which makes initiating a voice call always a mere click away. Readers who use Microsoft Teams will know this as the “Meet now” button.

This raises questions like…

- Is viewing a VLE meant to be a solitary activity?

- Would this idea apply better to certain parts of the VLE more than others?

- Are there kinds of social interactions currently unavailable that this would unlock? Would they all be positive?

- How else might we make spontaneous connection possible when studying online?

- Should learning management systems be aiming to enable socialisation of knowledge (in the sense of tacit-to-tacit exchange as in SECI)?

- Would doing so in this way leave too much to chance?

- Might this play in to institutional nervousness around cheating?

What if we could see each other?

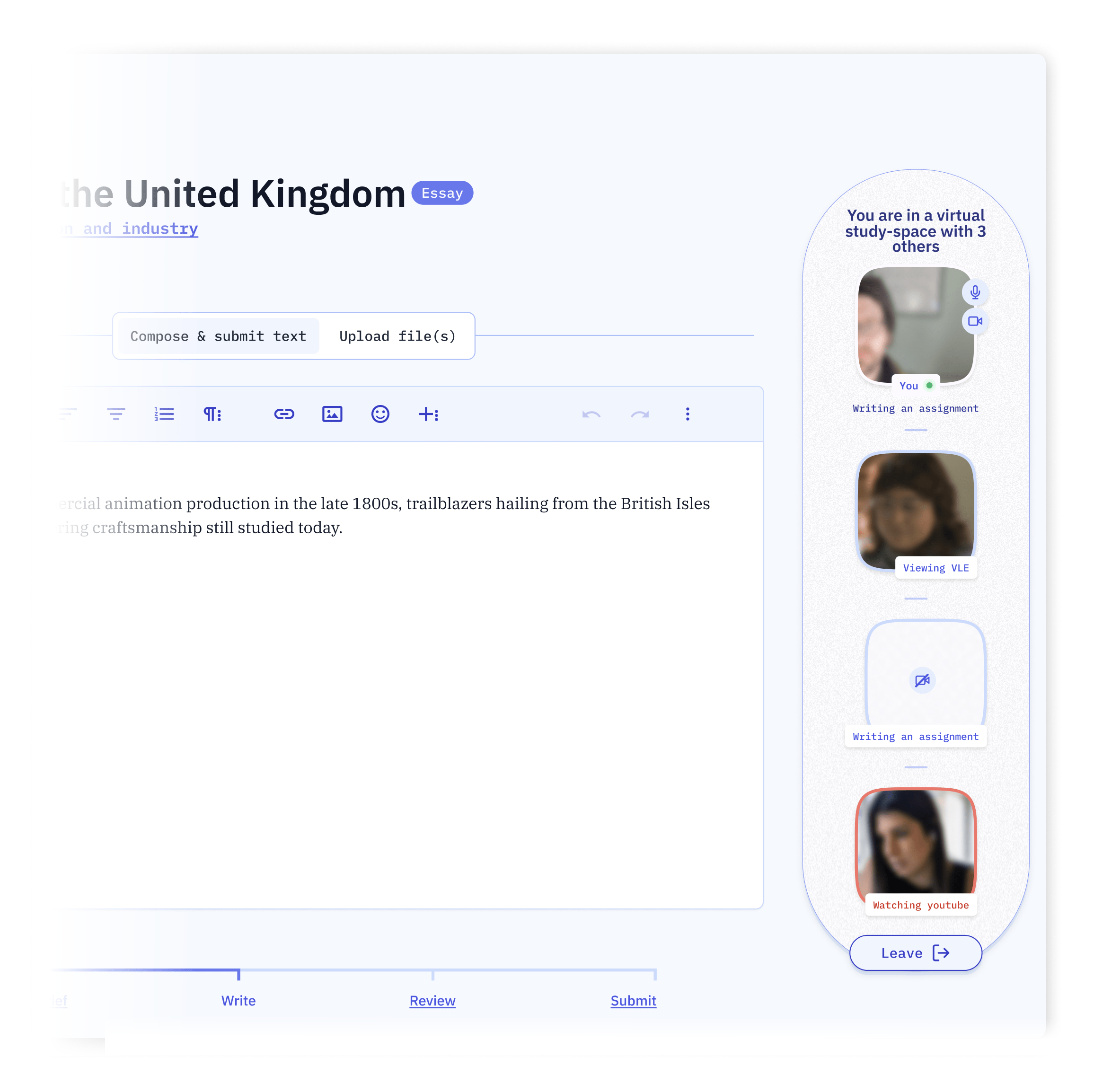

The virtual focus room aims to make shared presence within the VLE more akin to that of physical spaces like Libraries and other communal study environments.

It allows live video/audio connection between users of the VLE, but with the twist that you don’t need to be “in the same bit” of the VLE, or even working on the same thing. That dark blue widget on the right hand side of the mockup above would/could be persistent, staying there while the user moved around the VLE. Even jumping into different modules.

We observed that encountering others within a VLE would typically be predicated on a common assignment / module. Virtual Focus Room attempts to dispose of that, and bakes much more arbitrary social coworking into the VLE.

Social motivation

Our research told us that asynchronous systems were perceived as less sociable, in turn affecting motivation. By contrast, students told us that in-person social pressure was important for engagement for example in group projects. So Virtual Focus Rooms is not just about social connection, but about that relationship between shared presence and motivation.

At Jisc we’ve experimented with what is known as ‘focus sessions’ – we scheduled Zoom/Teams calls, where the aim was merely to log in, and carry on with your work while colleagues are also present. We’ve also written about some practice within the sector. Another model is “shut up and write”, and there are some productised interpretations like Caveday (facilitated work sessions) and Studyverse (student focussed),

Where Virtual Focus Rooms differs is that it makes it a built-in part of what the VLE – this makes it more available, but it also changes the role that VLE is trying to play for learners.

We looked at Discord, which lets you see what games others are playing. So as well as visibility of each other, what if Virtual Study Rooms displayed what you are up to? Proofreading or drafting an assignment, rewatching a lecture? Taking a break?

This raises questions such as…

- Could small, ad-hoc spaces be less intimidating for remote students to engage with colleagues, compared to larger scale video calls?

- What is positive social pressure for some may be anxiety-driving for others; what features might ensure psychological safety?

- Would study spaces have different impacts if they were sometimes inhabited by staff; or explicitly student-only spaces? Would students and institutional leaders have differing views on what is right in this regard?

- What safeguarding would an institution want to put in place in ad-hoc digital spaces?

- A VLE is an environment. It’s in the name. Post-pandemic, are people’s experiences and expectations for digital environments now different – higher? – in terms of video and social connection?

- Could the ideas within this concept be implemented in ways which remain discretionary for learners, and not a vehicle for unwanted surveillance?

What can we learn from YouTube?

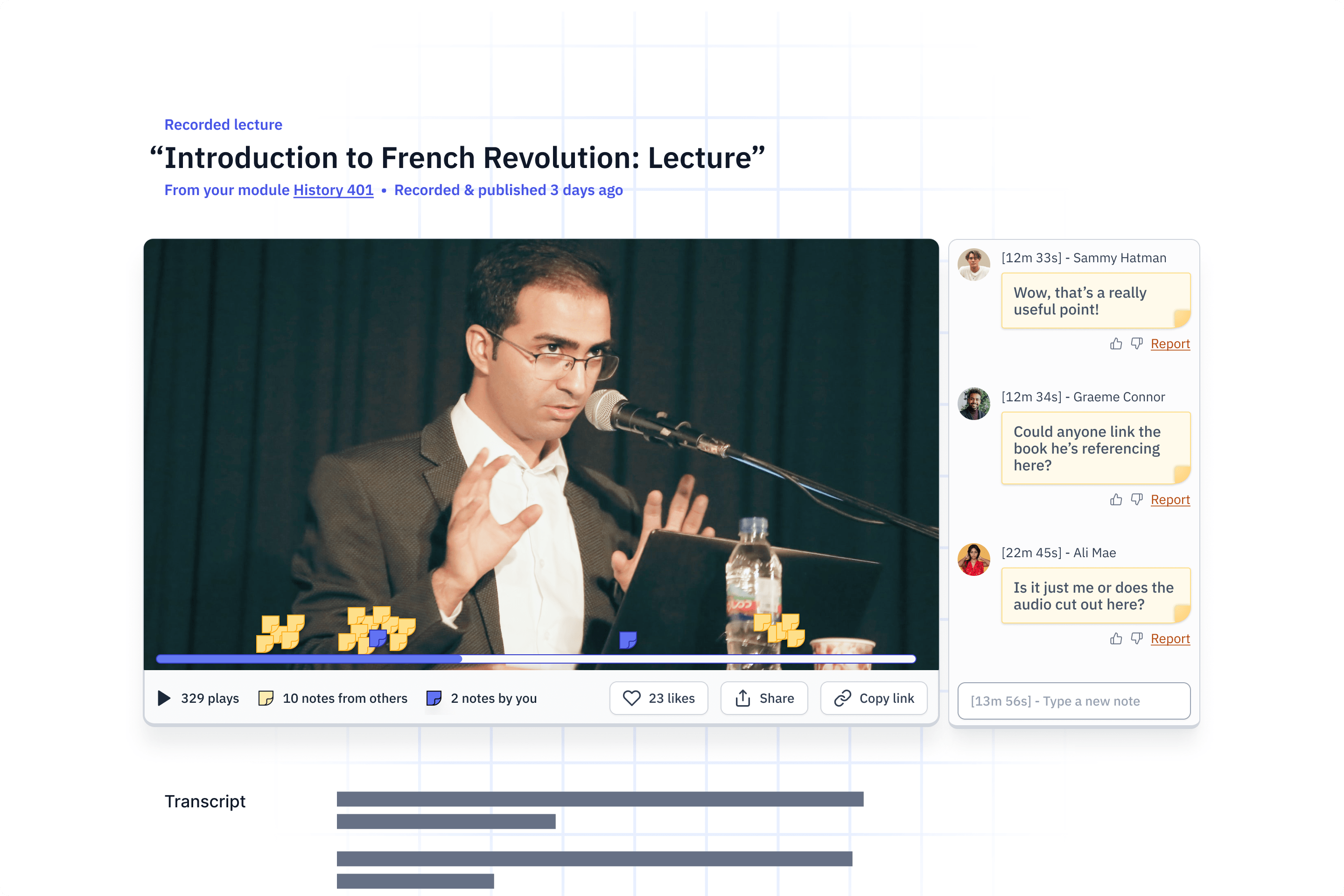

“Video notes” extends what we might expect from an embedded video file and adds personal and social insights.

Our research told us of the importance of peer instruction to students abilities in conceptual reasoning and problem solving. We also reflected on our finding that large video calls caused some students to be nervous to engage.

We also drew upon existing technologies. We noted a recent flurry of AI products has generated tools which seek to add value to video by helping to process it, like videohoghlight.com, and summarize.tech.

Social marginalia

With Video Notes we thought about the temporal nature of lecture notes – a note being a thing that happens at a given moment. Notes needn’t just be a reminder of what was said: a note can be inspired by something in a lecture, and timestamping it allows you to trace the origin of a thought. Notes could be made private or visible to others.

This model is possible, lookback.com is a user-testing tool which allows timestamped notes, and Panopto allows private and shared timestamped notes on lectures.

To extend this further we looked at the social signals that could be possible. If you’ve used YouTube you may have seen the “graph” that appears above the timeline, allowing you to see the most re-watched parts of a video.

The same thing be applied to lecture capture, or it could be based upon the amount of notes recorded against different timestamps. Whether the contents of the notes were shared or private could be considered, but either way as with the YouTube replay chart, the actions of the crowd creates new information for individuals.

This raises questions like…

- When we talk of “lecture capture”, are we thinking of lectures as the transmitted sound/imagery, or some of the broader parts of that experience?

- What kinds of actions do users take while receiving information from presenters? VLEs enabling these actions?

- Where else could crowd actions add information for the individuals? g..

- In a sea of links, which ones are most people clicking on?

- Which items in the reading list are getting least action, and therefore might yield some unique insights for my essay?

- Should a user’s lecture notes only ever be private? Should they be enabled to share them? What learning opportunities does this stifle, and create?

Stay tuned for the next part in this series, exploring more concepts and possibilities within the VLE.